Unmasking the Pandemics: 1918’s Spanish Flu, COVID-19, and the Germ Theory Debate

I. The 1918 “Spanish Flu”: Origins and Oversights

1. Misattributed Beginnings

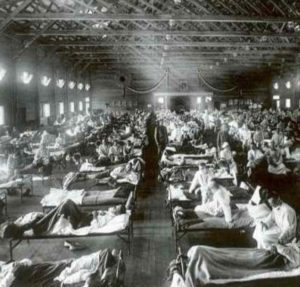

The commonly held belief that the “Spanish Flu” originated in Spain is historically inaccurate. In reality, one of the earliest recorded outbreaks occurred in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918. Local physician Dr. Loring Miner alerted the U.S. Public Health Service to the unusual influenza strain, which exhibited higher virulence than typical seasonal flu. This strain spread rapidly to Camp Funston (Fort Riley), where thousands of troops were stationed and undergoing training to be deployed to Europe.

On March 4, 1918, the first officially documented case of the influenza occurred at Fort Riley. Within days, over 500 soldiers were hospitalized. These troops, unknowingly infected, were then deployed across the U.S. and to European fronts, effectively turning World War I into a global transmission mechanism.

Historical analysis, such as the work of historian John Barry (author of The Great Influenza), points to the rapid mobilization and global movement of troops as the main vector of the disease’s worldwide spread, not Spain.

2. Experimental Vaccination Programs and the Rockefeller Institute

In 1917, the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (now Rockefeller University) initiated an experimental vaccination program using a bacterial meningitis vaccine developed by Dr. Frederick L. Gates. The vaccine was administered to thousands of U.S. soldiers at Fort Riley. It consisted of a series of injections using inactivated strains of Neisseria meningitidis, but also included other bacterial agents.

While the vaccine was intended to prevent meningitis, some researchers and skeptics have speculated that it may have inadvertently introduced new pathogens or compromised immune responses. These concerns stem from later reports that the autopsies of many 1918 flu victims revealed signs of severe bacterial pneumonia, not just viral damage.

A 2008 study by Dr. Anthony Fauci and colleagues confirmed that the majority of 1918 flu deaths were due to secondary bacterial infections. These findings reignited questions about the unintended consequences of mass vaccination during wartime and whether the immune systems of soldiers were weakened by multiple vaccines, poor nutrition, and unsanitary conditions.

3. Media Censorship and the “Spanish” Label

During World War I, strict censorship laws such as the U.S. Sedition Act of 1918 prevented the press from reporting anything that could damage morale or the war effort. Countries involved in the war, including the U.S., UK, France, and Germany, suppressed news of the spreading illness.

Spain, a neutral country during WWI, had no such censorship. When King Alfonso XIII of Spain fell gravely ill in May 1918, the Spanish press freely reported on the outbreak, which led other countries to nickname the disease the “Spanish Flu.”

This misnomer has endured despite widespread recognition that Spain was merely the most transparent nation in its reporting. The label helped deflect blame from the U.S. and Allied military operations and obscured the origins of the pandemic for generations.

II. COVID-19: A Century Later, Similar Patterns

1. Emergency Use and Rapid Vaccine Deployment

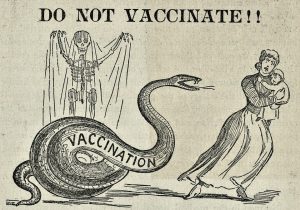

In response to the global outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020, governments and pharmaceutical companies raced to develop a vaccine. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) to Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines.

These vaccines bypassed the traditional multi-year testing timeline, moving from lab to large-scale human trials in less than a year. While supporters hailed this as a scientific triumph, critics noted that the compressed timeline left significant gaps in long-term safety data.

Adverse events, ranging from myocarditis to blood clotting disorders, were reported in various countries. The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) in the U.S. logged tens of thousands of entries, prompting debates about transparency and risk-benefit analysis.

2. Media Control and Suppression of Dissenting Voices

Social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter (now X), and YouTube adopted aggressive content moderation policies to limit the spread of “misinformation” related to COVID-19. Posts questioning vaccine safety, advocating for early treatments like Ivermectin or hydroxychloroquine, or challenging mask mandates were removed, labeled, or shadow-banned.

Medical professionals who voiced dissent—such as Dr. Robert Malone, Dr. Peter McCullough, and the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration—faced professional censorship, deplatforming, and even job loss. These actions raised critical concerns about the suppression of open scientific debate and the growing influence of unelected tech entities over public discourse.

3. Financial Motives and Big Pharma Profits

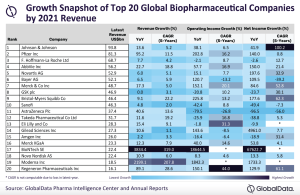

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented profit windfall for pharmaceutical companies. Pfizer reported over $80 billion in revenue in 2021, with $36 billion coming from its COVID-19 vaccine alone.

The centralized global push for vaccine procurement and deployment—often tied to government mandates and digital health passes—highlighted the powerful nexus between regulatory agencies, global health organizations (like the WHO and GAVI), and Big Pharma. Critics questioned the impartiality of policies driven by institutions with deep financial ties to vaccine manufacturers.

III. Germ Theory vs. Terrain Theory: Two Competing Models of Disease

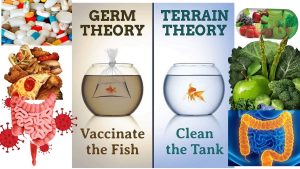

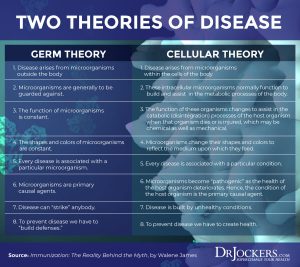

1. Germ Theory

Popularized by Louis Pasteur in the 19th century, germ theory posits that specific microorganisms cause specific diseases. It gave rise to vaccines, antibiotics, antiseptic techniques, and a revolution in sanitation. The theory has been foundational in modern medicine.

However, Pasteur’s deathbed admission—”the microbe is nothing; the terrain is everything”—has fueled speculation that even he recognized the limitations of his model. Germ theory has been critiqued for its reductionist focus, often ignoring the body’s internal health and immune function in disease susceptibility.

2. Terrain Theory

Antoine Béchamp, a French biologist and rival of Pasteur, proposed that microbes naturally exist in the body and become pathogenic only when the internal environment (or “terrain”) is compromised. According to this theory, disease is not caused by invading germs but by imbalances in the body’s natural terrain due to poor diet, stress, toxicity, and emotional/spiritual disconnection.

Béchamp also introduced the concept of “microzymas”—tiny indestructible particles within cells that transform based on the body’s condition. Though largely dismissed by mainstream medicine, terrain theory has gained renewed interest in the holistic and functional medicine communities.

IV. Virology and Diagnostic Testing: What Are We Really Measuring?

1. PCR Testing Limitations

The Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test became the gold standard for detecting SARS-CoV-2. However, the test does not distinguish between live (infectious) virus and non-infectious viral RNA fragments.

Dr. Kary Mullis, inventor of the PCR technique, warned against using it for diagnosing infectious diseases. He emphasized that PCR amplifies genetic material to such an extent that almost any sequence can test positive under certain cycle thresholds (Ct).

High Ct values (above 35) are known to produce false positives, identifying people as “infected” even when they are asymptomatic and non-contagious. The lack of standardized Ct thresholds globally further complicated case tracking and policy decisions.

2. Questionable Virus Isolation Methods

Critics argue that many “isolated viruses” have never been truly purified or visualized in their entirety. Standard virus isolation involves growing cell cultures, adding patient samples, and observing cytopathic effects (CPE). However, these changes can occur from antibiotics, cell starvation, or lab conditions.

In COVID-19 studies, electron microscope images claimed to show SARS-CoV-2 particles often relied on complex interpretations. Some researchers contend that what is labeled a “virus” might instead be exosomes—cellular vesicles involved in communication and detoxification.

Such criticisms challenge the foundational assumptions of virology and point toward a need for more rigorous methodologies in proving viral causation.

V. Conclusion: Learning from the Past to Understand the Present

The 1918 and 2020 pandemics offer a mirror reflecting our ongoing struggle with disease, science, and authority. From rushed vaccines and media manipulation to debates about the very cause of illness, these events compel us to question official narratives.

Understanding terrain theory, scrutinizing diagnostic methods, and exposing financial entanglements between governments and pharmaceutical giants are essential steps toward reclaiming bodily sovereignty and rebuilding trust in public health.

Whether one accepts or questions virology and germ theory, it is clear that informed consent, transparency, and open scientific dialogue are the true pillars of ethical medicine.

——————————————————————————————————————–

References and Citations (Selected):

- Fauci, A., Morens, D., & Taubenberger, J. (2008). “Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: Implications for pandemic influenza preparedness.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases.

- Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza.

- FDA.gov official EUA announcements

- PMC articles on PCR test methodology

- Dr. Sam Bailey & Dr. Andrew Kaufman on virus isolation

- Rockefeller University archives

- WellnessMovementServices.com (terrain theory overview)

This exposé is offered to encourage critical inquiry, honor the historical record, and empower individuals to think independently. The path to truth requires courage, humility, and the willingness to confront uncomfortable realities.