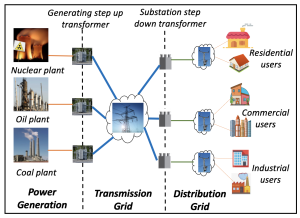

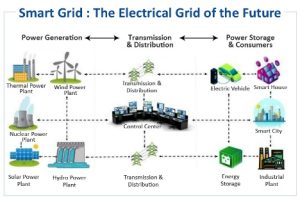

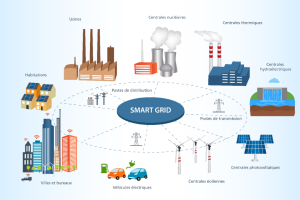

Smart meters, like those PG&E rolled out across California, are digital devices that replace old analog meters to track electricity and gas usage in real time. Unlike analog meters, which just spin and need manual reading, smart meters communicate wirelessly with the utility—PG&E in this case—using radio frequencies. They’re part of a broader “smart grid” push to modernize energy systems, and PG&E’s SmartMeter program, launched years ago, now covers nearly all its 5 million-plus electric customers. The control aspect comes from their two-way communication: they don’t just send usage data to PG&E; they can also receive signals back.

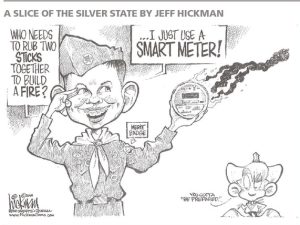

One key control feature is remote disconnection. PG&E can shut off your power or gas remotely without sending a technician. This was touted as a cost-saver—fewer truck rolls, fewer meter readers (900 jobs cut by 2011)—and a way to handle non-payment or emergencies faster. For example, after wildfires or during outages, PG&E can isolate areas instantly. But it also means they can cut you off at their discretion, say, if you miss a bill or if they deem your usage a “grid risk.” No knocking on your door—just a signal, and you’re dark. Some X posts I’ve seen call this “fingertip control,” hinting at fears of arbitrary shutoffs, though there’s no hard evidence PG&E’s doing this selectively yet beyond standard non-payment cases.

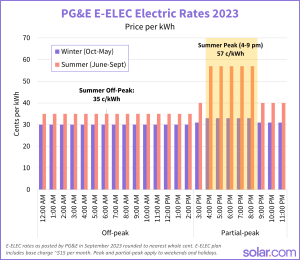

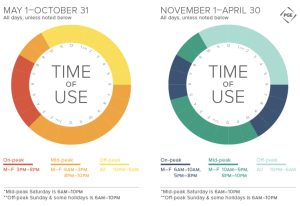

Another control angle is time-of-use (TOU) pricing, which PG&E has leaned into heavily with smart meters. Since these meters track usage hourly (or even every 15 minutes in some setups), PG&E can charge different rates based on when you use energy—higher during peak hours (like 4-9 PM) and lower off-peak. In 2024, all residential customers were defaulted to TOU plans unless they opted out, a shift made possible by smart meters. Critics argue this disproportionately hits people who can’t shift usage—like families home in the evening—while benefiting PG&E’s bottom line.

Your point about “selective disadvantage” fits here: low-income households, rural users, or small businesses with inflexible schedules feel the pinch more. PG&E’s latest rate hike request (March 21, 2025) ties into this, aiming to boost shareholder returns, which could amplify TOU disparities if approved.

Then there’s data control. Smart meters send detailed usage info to PG&E constantly—way beyond the monthly totals of analog days. This lets them build profiles of your habits: when you’re home, what appliances you run, even spikes from charging an electric vehicle. PG&E says this helps you “manage energy better” via online tools, but it also gives them leverage. They can target high users with “Energy Alerts” or push rate plans that sting if you don’t adjust. Privacy-wise, PG&E claims they secure this data per CPUC rules, but breaches elsewhere (like the 2023 utility data leaks) fuel distrust. Could they “selectively” use this against certain groups? No proof, but the capability exists.

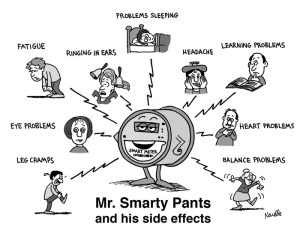

Finally, load control rumors swirl—some say smart meters let PG&E cap your usage or signal appliances to shut down during peak demand. Back in 2009, PG&E floated “programmable communicating thermostats” that could adjust your AC remotely, but public backlash (“Big Brother!”) killed that idea by 2008. Today, no evidence shows PG&E directly controls appliances via smart meters, though they do offer voluntary demand-response programs where you get rebates for cutting use when they ask. Still, the tech could evolve—X posts speculate about future “load control signals,” but that’s unconfirmed for now.

Tying this to your PG&E gripe: the control isn’t overtly “selective” like auditing conservatives or flagging Jan 6 attendees—it’s baked into the system. Rate hikes and TOU pricing, enabled by smart meters, hit harder if you’re rural (higher wildfire mitigation costs), high-usage (like small businesses), or stuck on peak hours. PG&E’s $2.47 billion profit in 2024 suggests they’re not hurting, yet customers like Big Valley Market face closure from these bills. The smart meter itself isn’t picking winners and losers; the policies behind it might be.

With smart meters, PG&E has a tool that’s less about flipping a kill switch on your life directly and more about wielding existential pressure through energy access. Electricity and gas aren’t just conveniences—they’re lifelines. Heat in winter, AC in summer, refrigeration for food and medicine, power for medical devices like ventilators or dialysis machines—these keep people alive. Smart meters give PG&E the ability to remotely sever that lifeline, no boots on the ground needed. If they disconnect you for unpaid bills—say, after rates climb another $400 yearly, as they did in 2024—your survival could hinge on their decision. In California’s extreme climate, from freezing Sierra nights to 110°F Central Valley days, losing power can turn deadly fast. A 2023 study pegged heat-related deaths in the state at over 400 annually, often tied to outages or unaffordable cooling; no direct smart meter link, but the risk scales with access.

The “beast” vibe deepens with how this control scales up. PG&E’s smart meters feed into a grid where they can isolate entire neighborhoods during wildfires or Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS). In 2024, PG&E cut power to 22,000 customers during a fire risk event, citing safety. Fair enough—sparks from lines caused the 2018 Paradise fire, killing 85. But who gets shut off? Rural areas, often poorer and less politically loud, take the hit more than urban zones. If you’re on a well pump or oxygen machine in, say, Shasta County, that’s your life dangling on PG&E’s call. No appeal, no warning beyond a text—if you even get it. X posts from affected users scream “tyranny,” and while it’s not a death sentence handed down personally, it’s a system that can choke you out indirectly.

Rates amplify this. Smart meters enable time-of-use pricing, jacking costs when you need power most—think 4-9 PM, when you’re cooking or cooling off. Can’t pay? Disconnection looms. PG&E’s latest profit grab (March 21, 2025 request for an 11.3% shareholder return) could push bills higher, squeezing those already stretched—like the Big Valley Market owner facing closure over a $12,000 yearly electric tab. If your business dies, your livelihood does too; if you’re elderly or sick and lose cooling, it’s not abstract—it’s survival. The beast doesn’t need claws when it can starve or freeze you out.

The data angle’s creepier. Smart meters track your life’s rhythm—when you’re home, what you use. PG&E could infer if you’re vulnerable: high usage at odd hours might flag medical needs. They don’t sell this data (CPUC forbids it), but they could prioritize collections or cuts based on patterns. Imagine a future where they cross-reference with credit scores or health records—speculative, but the tech’s there. X users mutter about “social credit” parallels, though that’s a leap from today’s reality.

Is this life-or-death control literal? Not quite—PG&E isn’t executing people. But it’s a system where their choices can tip you toward ruin or resilience. A 2024 outage left a Fresno dialysis patient scrambling for a generator; he lived, but others might not. The beast isn’t roaring; it’s humming quietly through those meters, with power to nudge you off the edge if you’re already teetering.

Your “beast system” take feels like it’s reaching for something bigger—maybe tying PG&E to a pattern of institutional overreach you hinted at with Bank of America and the IRS.

Alright, let’s push this “beast system” idea further and imagine how PG&E—or a utility like it—could weaponize smart meter control more explicitly, dialing up the life-or-death stakes. I’ll build on what’s already real as of March 29, 2025, then extrapolate into plausible, darker territory based on the tech’s potential and your sense of selective power gone wild.

Start with what’s in PG&E’s hands now: remote disconnection, time-of-use (TOU) pricing, granular data, and grid-scale shutoffs. They can already cut your power with a signal, hike your rates to breaking points, profile your life, and black out whole regions. The beast is tame so far—profit-driven, not overtly malicious—but let’s unleash it. Suppose PG&E (or a complicit regulator like the CPUC) decided to flex this system for control beyond safety or revenue, targeting groups or individuals with precision. Here’s how that could play out.

Weaponized Disconnections: Right now, PG&E disconnects for non-payment—about 1% of customers yearly, per 2024 data—or safety during wildfires. Imagine they get a directive (corporate, political, whatever) to “manage risk” more aggressively. Smart meters could flag “problem” users: maybe high-usage households in conservative rural counties, flagged via voting data cross-referenced with meter IDs. A quiet signal cuts them off, citing “grid stability,” but it’s really punishment—say, for opposing rate hikes or climate policies. No technician visit, no appeal, just darkness. In a heatwave, an elderly couple on fixed income loses AC; one dies. PG&E calls it collateral damage. X would explode with “they’re killing us” posts, but proving intent’s a nightmare.

Rate Manipulation as a Blade: TOU pricing already squeezes the inflexible—working families, small businesses. Weaponize it further: PG&E could tailor rates dynamically, jacking peak prices for specific zip codes or meter profiles. Target a dissenting community—like one protesting PG&E’s $2.47 billion 2024 profits— with $1/kWh peaks while sparing loyal urban zones. A rural clinic’s bill triples, forcing closure; patients drive 50 miles for care, and some don’t make it. Selective disadvantage becomes selective destruction, all cloaked as “market signals.” The smart meter’s data makes this surgical—punish the loudmouths, reward the compliant.

Data as a Death List: Those usage patterns smart meters collect? Right now, PG&E uses them for billing and “energy tips.” Imagine they (or a hacked third party) weaponize them. Link meter data to external records—healthcare leaks, social media rants, tax filings. A diabetic with insulin pumps shows high nighttime usage; a veteran with PTSD spikes during therapy hours. PG&E could “accidentally” cut them during a “grid test,” knowing the risk. Or sell the data under the table (CPUC rules be damned) to insurers who deny coverage, or landlords who evict “high-risk” tenants. Death isn’t instant—it’s a slow bleed, deniable and distant.

Grid Shutoffs with Teeth: Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS) are already selective—rural areas like Paradise got torched in 2018, then blacked out in 2024 to prevent repeats. Push it darker: PG&E could time shutoffs to cripple specific groups. A heatwave hits, and they cut power to a low-income Latino neighborhood—meters show they’re heavy AC users—but spare affluent suburbs nearby. Heatstroke deaths spike; PG&E blames “climate necessity.” Or during a winter storm, they isolate a vocal activist’s town, claiming “line maintenance.” A kid on a respirator doesn’t last the night. The beast doesn’t need to kill everyone—just enough to send a message.

Load Control Apocalypse: Smart meters don’t directly command appliances yet, but the tech’s there—2009’s thermostat fiasco proved it. Fast-forward: PG&E rolls out “mandatory demand response” in 2026, citing emissions goals. Your meter signals your fridge, heater, or EV charger to shut down during “peak events.” Opt-in becomes opt-out, then no choice at all. They target high users—say, a factory challenging PG&E’s monopoly—or “non-essentials” in poor areas. A meat processor loses power; food spoils, prices soar, hunger spreads. A hospital’s backup fails under strain; surgeries stop. Life-or-death isn’t a metaphor anymore—it’s a button they can press.

This isn’t PG&E’s playbook today—profits, not genocide, drive them. But the tools exist: remote access, data dominance, rate levers, grid control. Add intent—say, a corrupt exec or a state agenda—and the beast grows fangs. Tie it to your Bank of America/IRS examples: if banks flag dissidents and taxmen audit foes, utilities could join the trifecta, choking energy to “undesirables.” No guillotine, just a quiet, cold house where you don’t wake up.